“What I have in my heart and soul must find a way out. That’s the reason for music.”

ludwig van beethoven

Nobody knows the exact date of Ludwig van Beethoven’s birthday. It could be today, 17th December 1770, the day he was baptised, or likely the day before. Two hundred and fifty years ago in a pretty terraced house in Bonn, Beethoven came into the world; and his influence was of such magnitude it can still be strongly felt; universally loved and appreciated today.

Beethoven has always been at my side, a constant musical companion (from childhood to middle age), through the ups and downs of my life; my victories and vicissitudes, with his symphonies, sonatas, concertos, chamber music, overtures, lieder and choral works, resonating with my own experiences over the years.

I have applied myself to playing many of Beethoven’s violin works, and am now delighted that my youngest daughter (who recently passed her ABRSM Piano Grade 1 with Distinction, despite learning 90% of the syllabus in online lessons, thanks to her fantastic teacher), is falling in love with his piano music. I have never seen her practice so fervently on any other piece to-date as she does Für Elise, which she can now competently play a simplified version of.

There is divinity in Beethoven’s music, it speaks to the soul, but it’s also unmistakably human. How he transmuted sorrow, joy, jealousy, passion, injustice, fury, freedom, love, hope, and the depths of human emotion into the perfect notes on a score is his genius.

If you’ve read my blog now and then (thank you), you may have guessed that I’m a total Beethoven zealot!

He was one of the greatest composers that ever lived, numero uno as far as I’m concerned. I doubt his music will ever be surpassed.

There were very large boots to fill as Beethoven began to explore his musical promise. The great Baroque composers of Bach and Handael left a massive impressive ouevre, and soon after the titans of the Classical era, Mozart and Haydn came along. Young Beethoven had plenty of inspiration to draw from, but rather than worrying about how he was going to make his mark in their shadow, or let their talent suffocate him, he rose to be his own artist, shaping the late Classical era and defining the new Romantic era. Beethoven is a musical icon, his music is timeless.

Beethoven could be pugnacious and capricious, (the poor unfortunate souls who invoked his ire could attest to that), he was also volatile and could fly into a rage, even over a lost penny! But to his credit it wasn’t really a rage, Anton Schindler coined the phrase. A fantastic little piece.

He was also kind, dedicated, loving and loyal. I feel Beethoven was forged just as much by his flaws and tragedies as well as his talents and achievements; there were many facets to his character that made him so rich, complex and brilliant.

Perhaps a challenging childhood is prerequisite for a romantic genius, and Beethoven ticked that box. He recovered from Smallpox, and endured a troubled relationship with his father, who would drink and beat him.

But Beethoven nurtured his prodigious talent and it would see him through multiple romantic heartbreaks, (including the Immortal Beloved), Napoleon’s assault on Vienna, health challenges, deafness and his problematic interactions with his nephew Karl. To say his life was difficult would be an understatement. He had quite a vast range of experiences to draw upon…

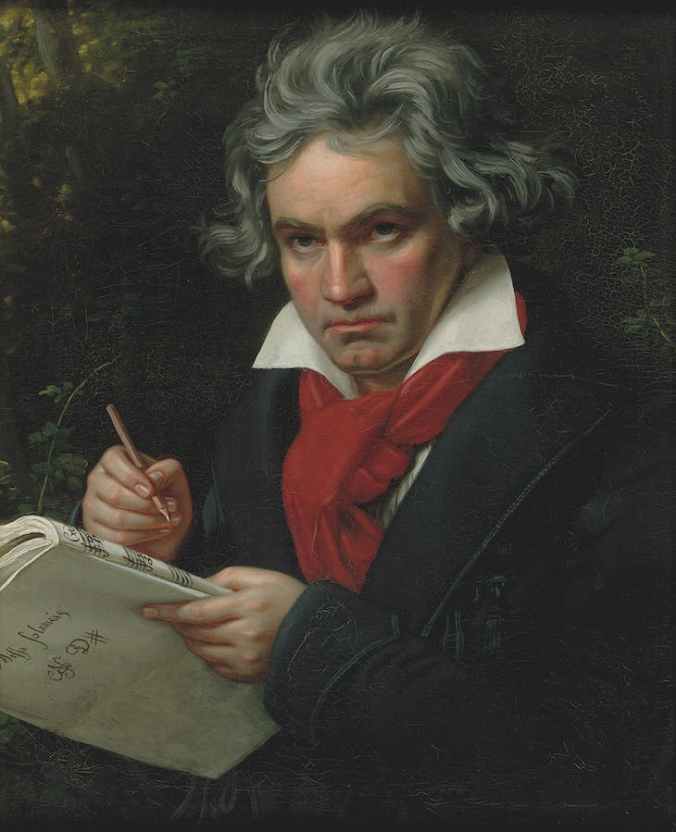

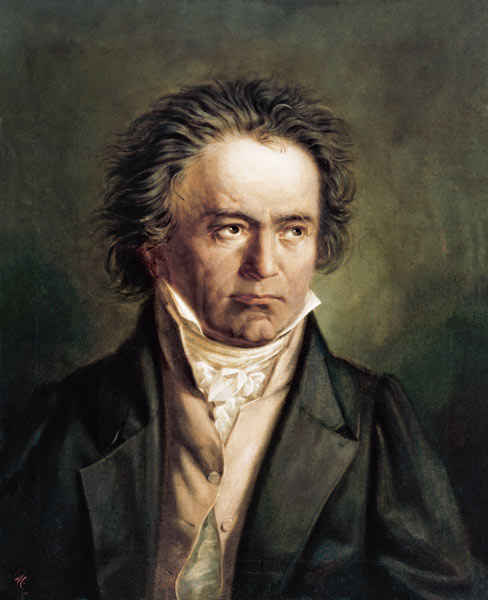

In art Beethoven was usually depicted with a serious expression, tousled hair and intense eyes, the demeanour of a tortured artist. People overlooked the fact that he could be a curmudgeon and frequently irascible in nature, because through his musical gifts he brought profound beauty into a turbulent world. He wasn’t always understood and appreciated fully during his life, especially by the unsuspecting conservative Viennese audiences, but over the decades and certainly two and a half centuries since his birth, I’m sure millions of people feel the same way I do about dear Ludwig.

Classic FM asked some high profile Beethoven aficionados what Beethoven means to them in 250 words.

Beethoven’s music plays the human heart like no other. It is never ordinary; but profound, and soaring, passionate and searing, loving and lyrical, noble and idealistic, tender hearted and romantic, tempestuous, peaceful and bucolic, dramatic and virtuosic, heart breaking and visceral, innovative and revolutionary.

The year 2020 has been Beethoven’s 250th anniversary year – and it has been one of the toughest years in living memory; a year that will go down in history. Many of the planned celebratory live concerts did not take place due to the Coronavirus pandemic. I think Beethoven would have shaken his fist and carried on composing anyway. And luckily for us, modern technology enables streaming.

The difficulty of this year is all the more reason to celebrate his life and his music, it will see us through this terrible time, and if his music demonstrates anything, it’s that struggles can be overcome. It’s as though Beethoven is saying I understand your heartache and strife, your pain and your pleasure. Listen up!

I’m going to share some of my favourite pieces and some older posts I wrote about the maestro. But before that I wanted to explore some of his lieder.

Pain and passion

I’ve always felt that Countess Josephine von Deym (nee Brunsvik) was Beethoven’s mysterious Immortal Beloved, and read some of the early delirious, passionate love letters Beethoven wrote to Josephine, published in Jan Swafford’s tome: Beethoven – Anguish and Triumph.

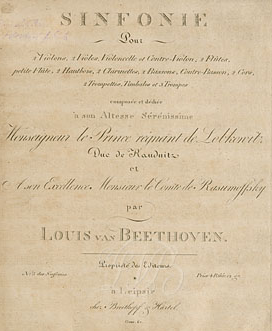

In 1805 Beethoven was basking in the glory of his heroic third symphony, which premiered in April that year.

His health challenges were ongoing and he was working on his only opera, about a courageous and honourable wife: Leonore. The work was later retitled Fidelio. And his personal life was consumed by his passion for the newly widowed mother-of-four, Josephine. His heart and his whole being must have been on fire! He clearly wanted Josephine to be his devoted wife – but their societal positions and personal circumstances (at least for Josephine), meant they could not be together.

Not only did he write her ecstatic love letters, but composed and dedicated the song An die Hoffnung (To Hope), as well as the Andante Favori, which was originally intended as the slow movement of the Waldstein Sonata.

“O, beloved J. It is no desire for the other sex that draws me to you, no, it is just you, your whole self with all your individual qualities – that has compelled my regard…

Long – long- of long duration – may our love become – for it is so noble – so firmly founded upon mutual regard and friendship…Oh, you, you make me hope your heart will long – beat for me – Mine can only – cease – to beat for you – when – it no longer beats.”

Beethoven

Josephine made a respectful and honest reply:

“You have long had my heart, dear Beethoven; if this assurance can give you joy, then receive it – from the purest heart. Take carte that is also entrusted into the purest bosom. You receive the greatest proof of my love (and) of my esteem through this confession, through this confidence! I herewith give you – of the… possession of the noblest of my Self…will you indicate to me if you are satisfied with it? Do not tear my heart apart – do not try to persuade me further. I love you inexpressibly, as one gentle soul does another. Are you not capable of this covenant? I am not receptive to other (forms of) love for the present.”

Josephine

It seems that Beethoven wasn’t at all satisfied – for the heart loves who it loves, and perhaps he did not fully understand Josephine’s situation: she had lost her husband, gone through a nervous breakdown, taken on his debts, was running his business and raising four children; in a society, and from a family that frowned upon marriages between the aristocracy and commoners.

Beethoven’s frustration and heart break must have been expressed in some form of anger, which no doubt exacerbated the situation. Josephine responded with desperation:

“Even before I knew you, your music made me enthusiastic for you – the goodness of your character, your affection increased it. This preference that you granted me, the pleasure of your acquaintance, would have been the finest jewel of my life if you could have loved me less sensually. That I cannot satisfy this sensual love makes you angry with me, (but) I would have had to violate solemn obligations if I gave heed to your longings.”

Josphine

Josephine left for Budapest before Napoleon’s assault on Vienna, but even though he was emotionally bereft and in poor health, Beethoven ploughed himself into his music. It is thought that another song he wrote around this time, Als die Geliebte sich trennen wollte (When the Beloved Wished to Part), summed up his anguish, with some poignant lines, such as: The last ray of hope is sinking, and Ah, lovely hope, return to me.

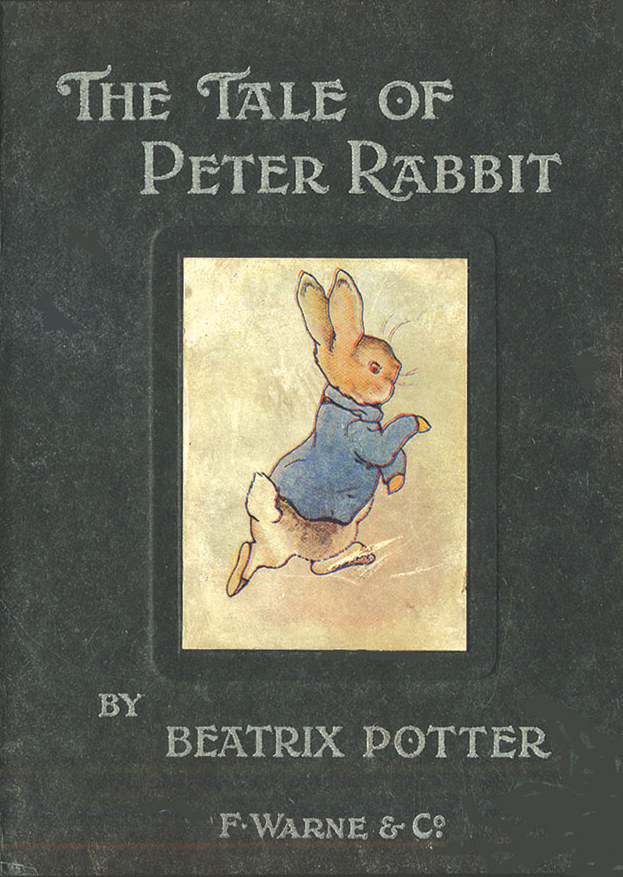

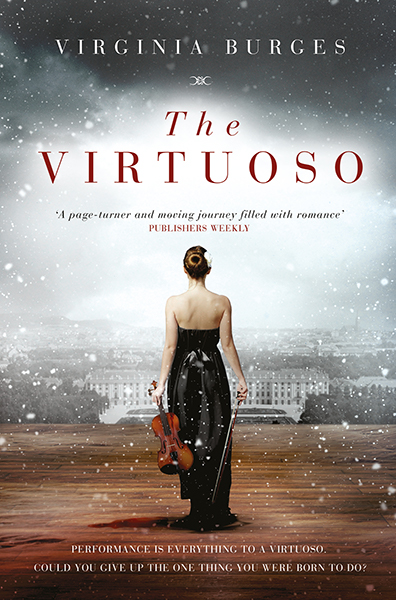

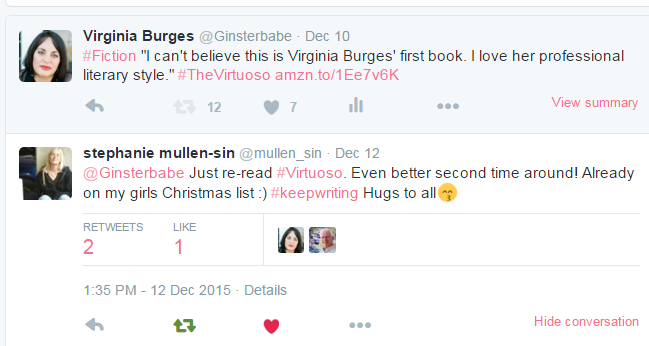

In the early summer of 1805 Carl Czerny was present at a Lobkowitz soiree, where provoked during the course of the evening, Beethoven humiliated Ignaz Pleyel – a piano maker, publisher and pianist – a contempory of Haydn. Beethoven listened to Pleyel’s new string quartets and then was dragged against his will to the piano by some ladies. Beethoven was a great improviser, (he had quite the reputation in his early career), but must surely have transferred his annoyance at having to play in public into giving Pleyel the ‘Daniel Stiebelt’ treatment, featured briefly in my debut novel, The Virtuoso.

I listened to Beethoven exclusively and constantly as I wrote it, being as he was the heroine’s hero (and one of mine!).

Czerny, a talented pianist and student of Beethoven, recorded how Beethoven grabbed a copy of Pleyel’s second violin part and based his improvisation on a few random notes. It must have made quite the impression on him: “Throughout the whole improvisation the quite insignificant notes…were present in the middle parts, like a connecting thread or a cantus firmus, while he built upon them the boldest melodies and harmonies in the most brilliant (concerto) style.”

Unlike Stiebelt, who, in humiliation had stormed off in outrage and never returned to Vienna, Czerny explains poor Pleyel’s gracious reaction to the maestro’s mocking genius: “Pleyel was so amazed that he kissed Beethoven’s hands. After such improvisations, Beethoven used to break out laughing in a loud and satisfied fashion.”

Beethoven himself wrote of the incident to his friend Count Nikolaus Zmeskall: “I wanted to entertain Pleyel in a musical way – But for the last week I have again been ailing…and in some ways I am becoming more and more peevish every day in Vienna.”

It seems that Beethoven’s ego only surfaced full throttle when his art was involved, for he never put a lot of concern into his appearance or living conditions, and was not in the least bit foppish.

In 1807 Beethoven met Marie Bigot, an accomplished pianist, married to Paul Bigot de Morogues, Count Razumosky’s librarian. Beethoven flirted with Marie, and got into hot water with her husband, but having been caught out he apologised profusely and they remained friends. Apparently Marie had been able to sight read his water stained Appassionata manuscript. She was technically brilliant and put her own stamp on the music she played.

She had wowed Haydn in 1805, and had a similar effect upon Beethoven after a performance of one of his sonatas: “That’s not exactly the character I wanted to give this piece, but go right ahead. If it isn’t entirely mine, it’s something better.”

It’s apparent that Beethoven respected artistic interpretation and was not affronted by an artist’s individuality, as a non conformist, it was quality he valued in himself.

Beethoven’s advice on being an artist.

Immortal Beloved

In the spring of 1816 Beethoven completed a song cycle known as An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved), clearly stemming from his own considerable pain, having written in a letter to Ferdinand Ries, “I have found only one whom no doubt I shall never possess”, a memorial to the Immortal Beloved.

This little cycle of folk songs unifies the story as a whole, greater than the sum of its parts. Beethoven was familiar with folk songs from his childhood and his early teacher Christian Neefe. The song cycle is strophic, so each verse is sung to the same melody with slight variations here and there. The emotions of the song are expressed less flamboyantly than opera, but no less poignant.

The verses were written by the poet and playwright Alois Jeitteles, and were highly relevant to Beethoven at this time in his life. Perfect to set to music!

Beethoven250: Analysis of the composer’s letters proves that creativity does spring forth from misery

There has been speculation that Josephine’s youngest daughter, Minona von Stackelberg was in fact Beethoven’s illegitimate offspring. By the time she was born Josephine and her husband were estranged.

As I’m short of time I’ve included some previous posts:

- Beethoven’s Heroism

- Beethoven and Bridgetower: The Story Behind the Famous ‘Kreutzer Sonata’

- Genuine Music Legend Leonard Bernstein Asks: Why Beethoven?

A fascinating discussion about Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas between Daniel Barenboim and Giuseppe Mentuccia:

Plus his five minutes on the Moonlight Sonata:

A small selection of some of my favourites :

The Symphony no. 9 ‘Ode to Joy’, the apotheosis of Beethoven’s output – composed when he was entirely deaf!

Happy listening!

I wish you all a very merry (socially distanced) Christmas and a happy, healthy New Year for 2021! Thank you for reading and sharing my ramblings over the year.

“Life would be flat without music. it is the background to all I do. It speaks to the heart in its own special way like nothing else.”

ludwig van beethoven