“How often did the master Joachim himself perform the work, how often did he teach it to countless pupils, and yet nowadays what is passed off as the Brahms Concerto no longer bears any relation to that [work].” ~ Heinrich Schenker

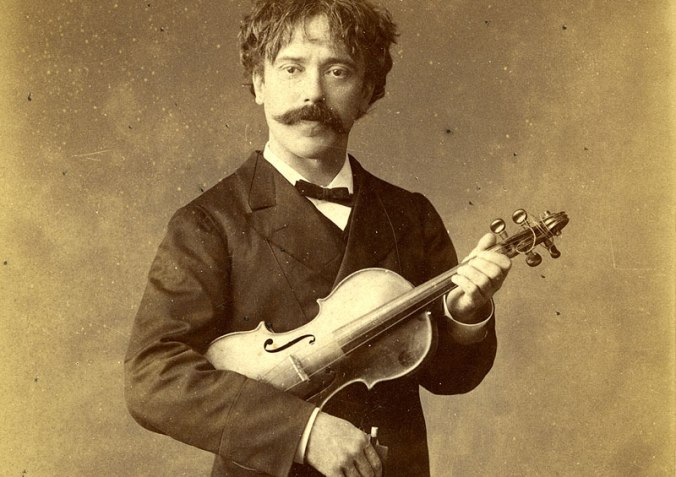

The name Joseph Joachim has been familiar to me for a very long time. I was aware that he was a celebrated and hugely virtuosic soloist, for I saw his name on many violin scores of other composers over the years as I progressed with my violin studies.

He had either arranged the piece for the violin and piano part, or written a cadenza. His musical pedigree shone from the pages of multifarious scores, but other than that I didn’t know anything else about him.

So here endeth much of my ignorance, as I attempt to shine the light of appreciation on Joseph Joachim’s life and achievements.

Whilst Joachim was much more famous for his playing career than his composing (as many of my revered candidates in this violin/composer series have been), this Austro-Hungarian maestro was an early trailblazer of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, and in a large measure responsible for its current popularity.

I love him for that alone!

His name is firmly established in the pantheon of violin greats; an exceptional talent on his instrument, and like many gifted musicians before him, he branched out into composing, conducting and teaching, where possibly his greatest legacy and influence still thrives.

Joseph Joachim: (28 June 1831 – 15 August 1907)

Joseph Joachim was born the seventh of eight children to Julius (a wool merchant) and Fanny Joachim on 28th June 1831, in Köpcsény, Hungary (present-day Kittsee, Austria). As an infant he survived the European cholera pandemic, which claimed almost 400 lives in the Pressburg region.

When Joseph was two years old the Joachim family moved to Pest, then the capital of Hungary’s thriving wool industry. His older sister had stimulated an early interest of music in him from her study of guitar and singing, and a toy violin given to Joseph by Julius seems to have been the beginning of a lifelong love affair with the violin.

Family of influence

Joachim’s cousin on his maternal side was Fanny (nee Figdor) Wittgenstein, who served as a surrogate mother to Joachim throughout much of his youth, mother of the industrialist Karl Wittgenstein, grandmother of the pianist Paul Wittgenstein and the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Joseph’s sister Johanna married Lajos György Arányi, a prominent physician and university professor in Pest who, in 1844, founded one of the world’s first institutes of pathology. Their granddaughters (Jospeh’s grand neices) were the distinguished violinists Adila (Arányi) Fachiri (1886-1962) and Jelly d’Arányi (1893-1966). Both had studied under Joachim’s protégé, the eminent Jenö Hubay.

Jelly d’Arányi is the protagonist of Jessica Duchen’s novel, Ghost Variations, a fictional tale around the true story of Robert Schumann’s long lost violin concerto, composed for her great uncle Joseph. This book is next on my reading list!

Joseph’s brother Henry followed in the same trade as their father, and settled in England, where he married Ellen Margaret Smart, from a prominent British musical family. Their son Harold Joachim (nephew of Joseph) was educated at Harrow College and Balliol College Oxford. A respected philosopher and scholar of Aristotle and Spinoza, his most well-known book was The Nature of Truth, (1906).

As an Oxford University professor he taught the American poet T.S. Eliot, who wrote: ‘to his criticism of my papers I owe an appreciation of the fact that good writing is impossible without clear and distinct ideas’ (letter in The Times, August 4, 1938).

He was also said to be a talented amateur violinist and married to one of Joseph’s daughters.

Harold’s sister Gertrude, (Joseph’s niece) married Francis Albert Rollo Russell, the son of British Prime Minister John Russell, and uncle of the philosopher Bertrand Russell.

Early Career

Joseph received his first violin lessons from Gustav Ellinger, a competent violinist but not the best teacher for the young prodigy, so Joachim’s parents’ placed young Joseph under the tutelage of Stanisław Serwaczyński, the concertmaster and conductor of the opera in Pest, who gave him a thorough grounding in the modern French School, by Viotti’s successors: Rode, Baillot and Kreutzer.

An early debut in Pest brought Joachim to the attention of an important benefactor: Count Franz von Brunsvik, a liberal aristocrat and a pillar of Pest’s musical community, and also the affection of his sister Therese.

Beethoven had dedicated his Appassionata Sonata, Op. 57 to von Brunsvik, who was among the earliest performers of Beethoven’s string quartets. Beethoven was also fond of Franz’s sister, Therese, to whom he dedicated his Op. 78 sonata, and their sister Josephine von Brunsvik, who I believe to have been Beethoven’s mysterious “Immortal Beloved.”

Vienna

The next stage of his musical development was to be in Vienna, where Joseph’s wealthy grandfather Isaac lived, as did his uncles, Nathan and Wilhelm Figdor.

Joachim had a shaky start with teacher George Hellmesberger senior, who doubted Joachim’s future as a virtuoso due to what he considered weak and stiff bowing. At this point Joachim’s parents (who had been in Vienna for his concert), decided that they would return with him to Pest and seek a new profession for their son.

Luckily for Joachim, the celebrated violinist Heinrich Wilhem Ernst was also in Vienna giving a series of highly publicised concerts, and when Joachim’s parents sought his advice he referred them to his own teacher: Joseph Böhm.

Böhm proved to be the best mentor to further develop Joseph’s talent. He was well respected as the father of the Viennese School of violin playing.

Robert W Eshbach writes:

Joseph Böhm played in many historically significant concerts, including a performance of Beethoven’s 9th symphony under the composer’s direction. He became an early advocate for Schubert’s chamber music, and, on 26 March 1828, he gave the premiere of Schubert’s opus 100 trio. Together with Holz, Weiss and Linke of the original Schuppanzigh Quartet, he performed Beethoven’s string quartets under the composer’s supervision. For Joachim, this direct personal and musical connection to Beethoven held a great and abiding significance.

Joachim’s training under Böhm was a true apprenticeship. In accepting him as a student, Böhm and his wife agreed to take him into their home just outside of Vienna’s first district, two blocks from the Schwarzspanierhaus where Beethoven had lived and died. For the next three years, for all but the Summer months, they would raise him in loco parentis, and train him in the practical skills of a professional violinist. Though not a violinist, Frau Böhm played a critical role in the Joseph’s musical upbringing, attending his lessons, and taking personal charge of his practicing.

I find it fascinating how the connections emanating from Beethoven’s life through his compositions, fellow musicians, friends, acolytes and protégé’s seemed to go full-circle in the life of Joseph Joachim!

Shortly before his own recital on 30th April 1843, Joseph had the benefit of seeing the Belgian violinist Henri Vieuxtemps perform in Vienna’s Imperial and Royal Redoutensaal, no doubt an inspiring event.

At his own recital to a burgeoning audience in the same venue, of the Adagio religioso and Finale marziale movements of Vieuxtemps’s fourth concerto in D minor, he made his debut with the Vienna Philharmonic.

Joachim left Vienna in the summer of 1843 to further his studies in Leipzig, where he was to audition for the composer Felix Mendelssohn.

Böhm relented, as his preference had been for his protégé to go to Paris instead.

In August that year Joachim appeared in a Leipzig Gewandhaus concert, with Pauline Viardot-García and Clara Schumann, playing an Adagio and Rondo by Charles-Auguste de Bériot.

London debut and critical acclaim

Under the guidance and mentorship of composer Felix Mendelssohn, the thirteen year old Joseph wowed an enthusiastic audience in the Hanover Square Rooms on 27th May 1844, with his performance of the hitherto rather unfairly maligned Beethoven Violin Concerto.

Vieuxtemps’s Beethoven performance had taken place in Vienna in 1834, but in London there had been no well received recitals of Beethoven’s only violin concerto.

After what must have been a poor performance in London in April 1832 by Edward Eliason, came this scathing review in Hamonicon:

“Beethoven has put forth no strength in his violin concerto. It is a fiddling affair, and might have been written by any third or fourth rate composer. We cannot say that the performance of this concealed any of its weakness, or rendered it at all more palatable.”

Many great violinists, including Ludwig Spohr, had rejected the work outright. “That was all very fine,” Spohr later said to Joachim by way of congratulations after a performance in Hanover, “but now I’d like to hear you play a real violin piece.”

Ouch! Perhaps it is poetic justice that Spohr’s own violin concertos, which only were popular during his lifetime, never reached the current pinnacle of Beethoven’s much loved and enduring work.

I wonder if Joachim realised all that was riding on his debut. Had he not played Beethoven’s ‘fiddling affair’ in such an outstanding manner, his career may have faltered and Beethoven’s only violin concerto may have forever remained in the shadows. That’s quite a lot of pressure to sit, even on the mature shoulders, of a young teenager.

Mendelssohn had put his own reputation on the line, having been invited over as the guest conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1843 and promptly suggesting the wunderkind Joseph Joachim to the society; who had a long-standing ban on child performers.

Eventually, after a few high level auditions, it was agreed that Joachim would play the Beethoven Violin Concerto.

A fabulous vintage recording of Beethoven’s VC played at a jaunty tempo, (Joachim Cadenzas) by fellow Hungarian, Joseph Szigeti, with the British Symphony Orchestra and Bruno Walter:

Joseph was paid the sum total of 5 guineas (with a guinea being equivalent to one pound, one shilling). Quite a disparity with today’s performers, (inflation not withstanding), but it was to be the opportunity of a lifetime.

Felix Mendelssohn in his elation wrote:

“… The cheers of the audience accompanied every single part of the concerto throughout. When it was over and I took him down the stairs, I had to remind him that he should once more acknowledge the audience, and even then the thundering noise continued until long after he had again descended the steps, and was out of the hall. A better success the most celebrated and famous artist could neither hope for nor achieve.”

The reviewer for the Morning Post enthused:

“Joachim, the boy violinist, astounded every amateur. The concerto in D, op. 61… has been generally regarded by violin-players as not a proper and effective development of the powers of their instrument… But there arrives a boy of fourteen [sic] from Vienna, who, after astonishing everybody by his quartett-playing, is invited to perform at the Philharmonic, the standard law against the exhibition of precocities at these concerts being suspended on his account. As for his execution of this concerto, it is beyond all praise, and defies all description. This highly-gifted lad stands for half-an-hour without any music, and plays from memory without missing a note or making a single mistake in taking up the subject after the Tutti. He now and then bestows a furtive glance at the conductor, but the boy is steady, firm, and wonderfully true throughout.

In the slow movement in C — that elegant expanse of melody which glides so charmingly into the sportive rondo — the intensity of his expression and the breadth of his tone proved that it was not merely mechanical display, but that it was an emanation from the heart — that the mind and soul of the poet and musician were there, and it is just in these attributes that Joachim is distinguished from all former youthful prodigies… Joachim’s performance was altogether unprecedented, and elicited from amateurs and professors equal admiration.

Mendelssohn’s unequivocal expression of delight and Loder’s look of amazement, combined with the hearty cheering of the band as well as auditory, all testified to the effect young Joachim had produced.”

On June 4th 1844, as news of his successful debut had spread, Joseph was asked to play for none other than Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort at a state concert in Windsor, attended by Emperor Nicholas of Russia, Frederick Augustus II, King of Saxony, the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel.

He performed Ernst’s Othello Fantasy, and de Bériot’s Andantino and Rondo Russe, (the second and third movements of his violin concerto No. 2 in B minor), accompanied by the Queen’s private band, and received a golden watch and chain from the Queen for his efforts.

The Liszt years, Hanover and touring

Mendelssohn’s sudden death in 1847 deeply affected Joachim, who was teaching at the Conservatorium in Leipzig and playing on the first desk of the Gewandhaus Orchestra with Ferdinand David.

In 1848 the renowned pianist and composer Franz Liszt invited Joachim to Weimar (once home to Goethe and Schiller) to join his circle of avant-garde musicians, encouraging him to compose. Joachim served Liszt as his concertmaster and seemed to embrace the new “psychological music” as he put it.

It was during his time in Weimar that he wrote his Violin Concerto in G minor, Op. 3, dedicated to his new mentor.

By 1852 Joachim had a change of heart and eschewed the direction of Liszt’s and particularly Wagner’s music of the ‘New German School’ and moved to Hanover. In 1857 he wrote to Liszt: “I am completely out of sympathy with your music; it contradicts everything which from early youth I have taken as mental nourishment from the spirit of our great masters.”

Under the generous patronage of King George V of Hanover Joachim was well paid and given the freedom to compose and undertake concert tours of Europe.

Performance repertoire and dedications

Joachim not only revived Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, but also championed Bach’s sonatas and partitas for solo violin BWV 1001 – 1006 and the much loved ‘Chaconne’ from the Partita No. 2, BWV 1004. Bach is staple canon for any modern violinist both pro and amateur.

How marvellous that Joachim’s good taste still prevails upon modern repertoire…

“The Germans have four violin concertos. The greatest, most uncompromising is Beethoven’s. The one by Brahms vies with it in seriousness. The richest, the most seductive, was written by Max Bruch. But the most inward, the heart’s jewel, is Mendelssohn’s.” ~ Joseph Joachim

He studied the Mendelssohn violin concerto with the composer, and famously provided inspiration and composition feedback to Johannes Brahms, who wrote his Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77 for Joachim.

A marvellous documentary with violinist Gil Shaham about Brahm’s violin concerto and Joachim’s role in its creation and performance:

Brahms’s Scherzo for Joachim, the third movement of the F-A-E Sonata, a passionate rendition from Vengerov and Papian:

He also performed his own version of Tartini’s Devil’s Trill and Robert Schumann’s dedication, Fantasy in C Major for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 131, previously unknown to me.

A wonderful 1953 recording of the piece arranged by Joachim for violin and piano, with a rhapsodic performance by Russian virtuoso Leonid Kogan and pianist Andrei Mytnik :

Joachim and Clara Schumann undertook a recital tour in late 1857, performing in Dresden, Leipzig and Munich. They were also well received in London’s St. James’s Hall. Joachim performed yearly in London from 1867 to 1904.

“Then there was a violin solo by young Joachim, then as now the greatest violinist of his time; and a solo on the piano-forte by Madame Schumann, his only peeress! and these came as a wholesome check to the levity of those for whom all music is but an agreeable pastime, a mere emotional delight, in which the intellect has no part; and also as a well-deserved humiliation to all virtuosi who play so charmingly that they make their listeners forget the master who invented the music in the lesser master who interprets it! “~ Excerpt from Trilby, 1894, by George du Maurier

Friendship with Johannes Brahms and the Schumann’s

Through his friendship with Robert and Clara Schumann Joachim was able to introduce them to the twenty year old Johannes Brahms. They would all form a close and lifelong friendship, but not without their disagreements.

After many years of friendship and close collaboration, Brahms sided with Joachim’s wife at the time of their divorce. Joseph had accused Amalie of having an affair, but Brahms apparently had thought more highly of her chastity!

Their rift lasted a year, and was mended, at least partially, when Brahms composed his Double Violin Concerto for Violin and Cello.

The King of Cadenzas

Joachim wrote the cadenza as the dedicatee for Brahms’s violin concerto. Joachim’s cadenzas:

- Beethoven, Concerto in D major, Op. 61

- Brahms, Concerto in D major, Op. 77

- Kreutzer, Concerto No. 19 in D minor

- Mozart, Aria from Il re pastore, K. 208, Concerto No. 3 in G major, K. 216, Concerto No. 4 in D major, K. 218, and Concerto No. 5 in A major, K. 219

- Rode, Concerto No. 10 in B minor, and Concerto No. 11 in D major

- Spohr, Concerto in A minor, Op. 47 (Gesangsszene)

- Tartini, Sonata in G minor (Devil’s Trill)

- Viotti, Concerto No. 22 in A minor

Recordings of his cadenzas of Brahms and Mozart:

Hilary Hahn playing Joachim’s cadenza for the Brahms VC:

Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D Major K.218 – 1st Movement – Allegro with Henryk Szeryng, New Philharmonia Orchestra w/Sir Alexander Gibson (Joachim Cadenza at 7.05):

The Joachim String Quartet

Aside from his illustrious career as one of the most influential solo violinists of his era, Joachim also performed chamber works with his eponymous string quartet.

They gave recitals of Beethoven’s late quartets – high in difficulty and low in popularity, at least until revival by Joachim and his quartet members: Robert Hausmann (cello), Joseph Joachim (1st violin), Emanuel Wirth (viola) and Karel Halíř (2nd violin).

The Joachim Quartet performing in the Sing Akademie zu Berlin in 1903 – engraving based on a painting by Felix Possart

The Joachim Quartet was formed in Berlin in 1869 and quickly garnered a reputation as the finest quartet in Europe at the time. Joachim played in the quartet until his death in 1907.

Joachim’s former teacher, Joseph Böhm had been part of the quartet that had given the world premiere performance of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 12 in E-Flat Major, Op. 127, now in mainstream chamber repertoire:

The legendary music critic and theorist, Heinrich Schenker on his quartet in 1894:

“In the course of recent years, since Hellmesberger senior, the great quartet connoisseur and player, we found only one single quartet that could do complete justice to the demands of Beethoven, Mozart, and Schumann—that quartet was the Joachim Quartet from Berlin.”

Joseph Joachim’s vintage recordings

Please bear in mind that these recordings date back over a hundred and ten years and therefore sound scratchy and hissy by today’s standards, but they are just about clear enough to give you an idea of Joachim’s style.

It’s also worth noting that he was 72 years old at the time of these recordings, playing with swollen fingers and gout, so not in his prime!

Joachim’s Violin Concertos

Violin Concerto in One Movement in G minor, Op. 3 for Franz Liszt:

The so called ‘Hungarian’ violin concerto was composed in the summer of 1857, considered one of the great romantic violin concertos, written in the style of Hungarian folk music, which to Joachim, was inseparable to gypsy music.

Rarely performed, it has been described as “the Holy Grail of Romantic violin concertos” by music critic David Hurwitz.

The concerto premiered on 24th March 1860 in Hanover and was published in Leipzig by Breitkopf and Härtel in 1861.

“The critic Eduard Hanslick recorded Joachim as having been for some ten years the greatest living violinist. His review of the Concerto in the Hungarian Style was more guarded, describing it as too expansive, complicated and striking in its virtuosity to be evaluated at a first hearing.” ~ Keith Anderson

The performance I’m going to share is by Rachel Barton Pine, a musician I admire very much. She recorded the work on the Naxos label in 2003 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to high acclaim.

She was noted as saying that because the concerto is so challenging and lengthy (45 minutes+) practising and performing it was akin to “training to run a marathon”.

Excerpt from Grampohone Magazine:

In 1861, 17 years before Brahms produced his masterpiece in the genre, Joseph Joachim as a young virtuoso wrote his D minor Violin Concerto, In the Hungarian Style. He would later help to perfect the solo part of his friend’s work, but in his own concerto the solo part is if anything even more formidable, one reason – suggested in the New Grove Dictionary – that it has fallen out of the repertory.

Violin Concerto No. 3 in G Major, with Takako Nishizaki, Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Meir Minsky:

Other Compositions

Hamlet Overture, Op. 4 with Meir Minsky and the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra:

Overture in C major, performed by Maastricht Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Roland Bader:

The Overture in C major by Josef Joachim, was composed in 1896 for the imperial birthday of the Kaiser of Germany. It was first performed on 3 February 1896 in Berlin’s Royal Academy of Arts.

The delightful Hebrew Melodies, Op. 9 (after Impressions of Byron’s Songs) for viola and piano (1854–1855), with Hartmut Rohde and Masumi Arai:

Schubert’s Piano Sonata ‘Grand Duo in C Major, D 812’ arranged for orchestra by Joachim as Symphony in C:

Teaching Legacy

Probably Joachim’s most illustrious pupil was Leopold Auer, who himself went on teach some of the greatest violinists of the 20th century: Mischa Elman, Konstanty Gorski, Jascha Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, Toscha Seidel, Efrem Zimbalist, Georges Boulanger, Benno Rabinof, Kathleen Parlow, Julia Klumpke, Thelma Given, and Oscar Shumsky.

“Joachim was an inspiration to me, and opened before my eyes horizons of that greater art of which until then I had lived in ignorance. With him I worked not only with my hands, but with my head as well, studying the scores of the masters, and endeavouring to penetrate the very heart of their works…. I [also] played a great deal of chamber music with my fellow students.” ~ Leopold Auer

Other prominent virtuoso violinists who were tutored by Joseph Joachim included Jenő Hubay, Bronislaw Huberman, Karl Klingler (violinist of the Klingler Quartet and Joachim’s successor at the Berlin Hochschule), Klingler was the teacher of Shinichi Suzuki.

Franz von Vecsey, who studied with Hubay, then Joachim, became the dedicatee of the Sibelius violin concerto.

Andreas Moser (another of Joachim’s pupils), went on to become his assistant, helping to recover the original scores of J.S. Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, collaborating with Joachim on numerous editions. Moser wrote the first biography of Joachim in 1901.

Joachim’s Stradivarius Violins

From Wikipedia:

In March 1877, Joachim received an honorary Doctorate of Music from Cambridge University. For the occasion he presented his Overture in honor of Kleist, Op. 13. Near the 50th anniversary of Joachim’s debut recital, he was honored by “friends and admirers in England” on 16 April 1889 who presented him with “an exceptionally fine” violin made in 1715 by Antonio Stradivari, called “Il Cremonese”.

The provenance of the ‘Cremonese, Harold, Joachim’ is given in full detail on the intstrument’s listing in Tarisio. Currently housed at the museum in Cremona, here is a 2013 recital of Bach by Antonio de Lorenzi, and it sounds georgeous!

Joachim also played on the ‘Messiah’ 1716 Stradivarius which I have seen on display at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, on the list of the 12 most expensive violins in history.

He is no longer just a name on a score to me now – rather a fully fledged violin hero…